Joyce Wieland

/Joyce Wieland was a groundbreaking artist and cultural activist who used diverse media to explore feminism and Canadian identity.

Jane Lind, in her book Joyce Wieland Artist on Fire, quotes Joyce’s 1955 diary writing about the male-dominated culture. “Why for God’s sake cannot we girls be brought up to be humans instead of dependent wretches.”

She was born in Toronto on June 30, 1930 into a poor family. Her father died when she was young and her mother shortly afterwards. Joyce and her brother and sister had no home and little money for food until Joyce was in her early twenties.

She attended Central Technical School, where she met Doris McCarthy who taught at the school. McCarthy's artistic identity inspired Wieland to pursue her own and McCarthy encouraged that.

Weiland made a great contribution to the participation and acceptance of women in the art world. Much as Emily Carr broke ground years before, Joyce was the first woman to do a number of things in the art world.

She had her first solo exhibition in 1960 at the Isaacs Gallery in Toronto, making her the only woman that the prestigious gallery represented.

She was living and working in New York City and during that time, she also rose to prominence as an experimental filmmaker and soon, institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York were showing her films.

In 1971, Wieland's True Patriot Love exhibition was the first solo exhibition by a living Canadian female artist at the National Gallery of Canada.

That same year she returned to Toronto. She said she could not make art anymore in America due to its ideological orientation.

From an interview conducted by Kay Armatage that appears in Women and the Cinema, A Critical Anthology edited by Karyn Kay and Gerald Peary, Wieland says, “As I started being an artist I was influenced by many things, artists, et cetera, and by my husband, who influenced me not so much in style as in having my own well-developed outlook, philosophy.

“In a sense my husband's great individuality and talents were a catalyst to my development. Eventually women's concerns and my own femininity became my artist's territory.”

In the same interview Armatage asks, “Do you see this artist's territory that you've staked out opening out to other women besides you?

“Sure, why not. I would like to see them in that space, just as much as I would like to see us gain control of our government from the U.S. - or the Canadian Film Development Corporation.”

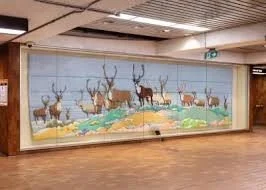

Barren Ground Caribou

A viewer at a gallery once asked Joyce, “Are you the lady who did this show? Well, we love it because it’s quilts and it’s about our country.” Joyce recollects in her CBC interview held at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Again, from Joyce Wieland Artist on Fire, Lind writes, “Several of her grade-twelve classmates told her about a labour strike at Eaton’s, she was interested and went with them to see what was happening. It may be this experience formed the seed for Solidarity, her film about the Dare strike in Kitchener, Waterloo (1972).”

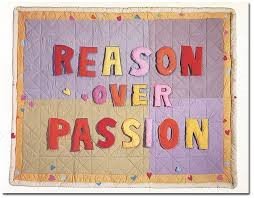

Johanne Sloan, in the Art Canada Institute article Reason Over Passion, writes, “The Reason Over Passion quilt attracted particular attention because of its direct reference to Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s quote, ‘Reason over passion – that is the theme of all my writing.’”

Sloan continues, “…deep-rooted prejudices were turned on Wieland when she showed this and other fabric-based and stitched artworks at the National Gallery of Canada as part of her exhibition True Patriot Love. One critic wrote scornfully about “Joyce the housewife” filling the gallery with pillows and quilts.”

Here is her filmography. Tea in the Garden, A Salt in the Park, Larry’s Recent Behaviour, Patriotism, Patriotism Part II, Water Sark, Barbara’s Blindness, Peggy’s Blue Skylight, Handtinting, 1933, Sailboat, Rat Life and Diet in North America, Dripping Water, Cat Food, Reason Over Passion, Pierre Vallieres, Solidarity, A and B in Ontario, Birds in Sunrise.

The Far Shore was her first and only narrative feature film with the cinematography done by Richard Leiterman.

Books about Wieland include Joyce Wieland: À cœur battant (Heart On) by Anne Grace and Georgiana Uhlyarik; Joyce Wieland: Artist on Fire by Jane Lind; Joyce Wieland: Life & Work by Johanne Sloan (Art Canada Institute); Joyce Wieland: A Life in Art by Iris Nowell.

Artist on Fire, directed by Kay Armatage, is a film about Weiland.

She received the honour of an Officer of the Order of Canada and in 1987, she was awarded the Toronto Arts Foundation's Visual Arts Award. She was also a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

In the Women and the Cinema interview Wieland later says to Armatage, “There are a lot of women in the avant-garde who are making films about feminist things and politics. …there's something depressing to me about it from what I know.... It's so masochistic. We have souls and spirits and we have the job of shamans, not the job of reiterating the misery that's been done to us... It's so neurotic, that stuff. What do those things do? You come out feeling even worse - it takes your energy away from you.”

Artist On Fire

The Art Gallery of Ontario held a retrospective Joyce Wieland: Heart On from June 27, 2025 to January 4, 2026.

Her funeral was held at St. George by the Grange Anglican Church in Toronto on July 8, 1998. Her ashes are interred in the wall of the church's memorial garden.

Sources

De Gruyter Brill, Stefan Ferguson

Queen's University, Marc Fortin

The Canadian Encyclopedia

Wikipedia

Cabbagetown People

Globe and Mail

University of Ottawa Press

New York Post