Acting for the camera.

This is the proper title.

At the end of the day, when we make movies, you are acting for the camera. The acting classes geared for film and TV must have this title.

Yes, read-throughs, first blocking for camera, camera rehearsal, masters, two shots all include other actors and lots of the set.

But once the camera is just on you, then it’s acting for camera. Television is often called talking heads and that’s done in close-up. Ultimate acting for camera.

The money shot.

It’s not like a play where the audience sees your whole body, all the other actors, the full set all the time. Feature films combine size — a key element of the form — with tight shots.

Your performance is influenced by how you’re photographed and lit. As the shot gets tighter, you are being directed more to fit the frame.

How they shoot you influences what your final performance looks like.

What is filmed — by the camera — is then pieced together by the editor and director. If it isn’t shot, it won’t be in the film.

You need to do your practice in front of a camera. Learn and master what is specific to acting for camera.

Don’t try to out-act a tree.

At the Moscow Art Theatre, the actors had to pretend to hear the cherry trees being cut down.

In film, you have real cherry trees to watch being cut down.

You’re an actor watching the trees being cut down, so what do you have to do? Nothing. Stand there and watch. The sound of the axe, the chips flying, and the woodcutter cutting all tell the story.

We cut to your face. You watch. You are us watching. We see your face — a blank face — and we attribute to your blank face what we think you’re thinking of the trees being cut.

Then we cut back to the tree being cut down. The tree is just there getting cut down. It plays its part.

Don’t do any more than the tree is doing or you’ll look silly. You won’t be believable.

In David Lean’s film Lawrence of Arabia, we see a rider on a camel against the horizon, and for two minutes they ride straight towards the camera. Perhaps one of the purest examples of how cinema can capture realism in a natural setting.

Omar Sharif had the good sense to do nothing but ride the camel.

Be a good student.

The teacher and the student both have obligations.

In the actor training circles, the actor talk is often focused on what the teacher was like and/or whether it was a good class.

Very seldom do the actors discuss their own work and more importantly whether they fulfilled their responsibilitieM.

Being a proper student is simply being a proper professional. The two are one and the same.

Class is a great opportunity to learn how to be professional.

If you are an emerging actor or an experienced one, you must cross the bridge from the old attitudes you had as a student in school over to new professional ones.

If you are in class, you must fulfill the minimum standards of being on time, prepared, having an opinion, working consciously, and asking questions. If you aren’t doing that, then the teacher cannot conduct the class as the dynamic is not achieved.

Here is the Merriam-Webster definition of dynamics: “the forces or properties that stimulate growth, development, or change within a system or process.”

You have to be one of those forces.

An acting class is not a service where you pay and expect to get good value for your money and then complain if you think you didn’t. That’s trouble.

If you’re going to class for a quick fix, you’re also in trouble. If you’re going to class because you haven’t been booking work lately and you think by going back for one class you’ll start landing jobs — you’re in trouble again.

Practising should be part of your actor’s life. Not the be all or the end all. You shouldn’t go trying to have a good class. More trouble.

Study and practice should be ongoing. Make it part of your cycle — class, audition, shoot, class.

Actors from the theatre come to film and TV classes wanting to learn how to act for the camera. Great. But they often cling to their narrative of “I’m a theatre actor, and camera is soooo different.” More trouble.

Let your narratives go and do the work.

The proper acting teachers are modern ones having assimilated the works of the masters. They continue to try to meet the demands of the present. They fulfill their duties and obligations.

As a student, you must ask questions. If the question is not appropriate, the teacher will say so. Then you must ask another question. It, too, may be inappropriate and the teacher will say so. Then the actor must ask, etc. . . . and on and on the training goes.

Just because you ask a question doesn’t mean you’ll get an answer.

Sometimes the teacher will answer the question.

The student must keep trying. The teacher keeps encouraging, critiquing, aiding, advising, and clarifying. That’s the back and forth.

It is an organic relationship with two equal parts even though the teacher has the authority.

Rights and privileges, duties and obligations.

It takes two to tango.

Practice in class.

Practice in class is different from auditioning or performing.

Practice is when you train your mind and body to do your acting. Learn to train properly. It will give rise to good habits.

Always put yourself first, your fellow actors second, and your teacher third. The experience should be yours.

By looking after yourself, so you can act your best, you fulfill being a good scene partner and a good member of the collective art form that is movie-making. Being nice and wanting your partner to like you don’t help.

Of course, you’re professional, respectful, and appreciative of one another’s work. That’s the expected norm.

Use class to practise small parts of your work. We grow in little bits. Step by step.

Try not to draw conclusions after experiencing good work. Resist the urge to try to remember what you did. The experience is in you. Keep going.

Just showing up for class makes it a good class, so there should be no need to impose your will upon it. That’s a path to working too hard.

Don’t try to be good or interesting.

As far as breakthroughs go, they come after repetitive proper practice and then — Wham! — you assimilate something. A breakthrough.

You can’t set out to have one.

The best routine as a professional is to practise, audition, shoot, and then come back again to practice.

Asking questions.

When preparing a scene, you should ask questions.

The answers aren’t the point; the point is the “asking of the questions” and getting your mind active. The questions will stimulate your imagination, which builds your confidence.

Any new idea that you conjure while preparing will always be with you. You don’t have to hold on to it. It’s in you.

Work properly so that your practice gives rise to good habits. Asking questions is part of proper practice.

Treat your mind with respect and know it is both powerful and delicate. Simply put: be nice to it. Asking questions should be a warm and friendly stroking of your mind, getting its best juices going, getting you going.

Ask questions.

“All rise!”

That’s what they say in court when the judge enters.

Well, they do on TV.

You might, like many actors, ask what you can do to be a better actor when you’re not filming or in class.

Observing. That’s something.

Go to a courtroom, hospital, or police station. Take a seat and look and listen. Stand around and see who you see.

All types you play on TV.

In the halls before court is in session you’ll see the accused, their families, the expensive lawyers in their expensive shoes, and the cheaper lawyers in their cheaper shoes. Cops in uniform, detectives in suits giving hard stares, court officials.

Go sit in court.

You can’t go inside the Emergency ward, but you can wait in the waiting room. Lots to see and experience there. People in pain. The health care system naked and bare.

Go to Obstetrics and see the babies. See the mothers. See the nurses. Listen to the crying.

Drop into a police station for a real reason or a made-up one. Ask a simple question. See what the cops in the station are doing. How the desk sergeant behaves.

Watch a cop direct traffic.

More movie types.

You’re observing yourself and others all the time as part of your work. These three particular workplaces can give you specific experiences.

Actor speak.

You don’t have to make any sense when you talk about your work.

Your talk should reflect whatever you are grappling with at that moment.

This doesn’t mean actors are nonsensical. No.

Directors and acting coaches need to be clear and make sense as they are running the overall in a horizontal sense. Seeing the whole picture.

Whereas you, the actor, are concerned in a perpendicular sense. Up and down with you and your character — narrow — not lengthwise of the whole movie or class.

Your concerns should be how to play truthfully. Voice that struggle.

In that context, you don’t have to make any sense. The directors — the good ones — will be able to follow any mutterings, grunts, howls, protestations, ramblings that you make and hopefully translate them to assist you.

When asking the camera operator about the size of a shot, you should be clear. Of course. Or telling wardrobe the sweater is too tight. Then you will make sense.

And when agreeing or disagreeing with your agent on what your fee should be, you want to make absolute sense.

But in the heat of putting up a scene, making sense is not what you should have uppermost in your mind. Getting it right, impressing others — that isn’t why you should be speaking.

When it comes to you actually speaking about your acting, it has to serve you first and communicate second.

Breathe as you breathe.

You have practised and heard so much about breathing.

We breathe all day long, so why the focus on something normal?

My experience is that it takes a long time — a lifetime — to assimilate the best breathing practices into your acting. To make it yours. To breathe as you breathe when in the scene.

Your goal should be to breathe as you when you’re acting. Not imitating the breathing you learned in voice class or yoga while acting. That’s a disconnect and your mind doesn’t like it.

The journey of practising better breathing to make it your own is key.

But you’ll probably — if you’re anything like me and other actors — have to act for many years carrying the disconnect of imitating learned breathing while acting. It isn’t a crime — it’s part of your development.

The point to know is that with conscious practice, your breathing will change qualitatively. It will become yours and it will include all the best practices you learned.

Once assimilated, your instrument will be trained and you will breathe well both technically and as you.

In acting and in life, the cycle goes impulse, breath, speech. That’s the linked journey you want to assimilate.

“I’m ready.”

Don’t start until you’re ready.

After “Action!” you need time between their order and your beginning.

It doesn’t have to be much time, but not jumping when the gun is fired is critical.

Always try to be on top of your work. To put yourself first.

To be in your own time and space that suits you. Not theirs.

It’s a question of an outlook and approach that is opposite of trying to please, of trying not to hold up time, of trying to get it right.

Going in your own time is qualitatively different.

This does not mean you hold up production. No. It doesn’t mean you don’t hit your mark in time or meet the dolly move or the camera push. Doing that is being professional.

It’s the mental conception that you start.

When do you go on set? When the Trainee Assistant Director comes and calls you and leads you on to set, chatting all the way, or when you decide to get up and leave your trailer and go in your own peace and quiet?

See if there’s a difference.

In acting class, we practise this by saying, “Say when you’re ready.” When they are ready, the actors respond, “I’m ready.”

When the actor says they are ready, they aren’t telling me or the other participants. They are telling themselves and saying it on voice. A verbal recognition of their starting.

We also do a hyper exercise highlighting starting. In that exercise, they can say ready or not ready.

We take the exercise further by having one partner challenge the other: “You’re not ready.” “I’m not going yet.” “You don’t want to start.” “You’re not ready.” “Yes! I’m ready” etc.

The actors must give their answer of what they’re actually feeling — ready, not ready.

There are a myriad of ways to do this — how you start — exploring your starting moment. That moment when you’re ready to act.

It is about time and how you control it.

Place.

One of the five acting questions you ask is “Where am I?”

What space are you in?

How to translate location or stage directions — “She crosses the room.” “She gets out of the car.” “She runs out the door.” — in an audition can be confusing.

Only use what’s indicated in the script that you like and helps you act. You do not need to show the producers that you know what location is written in the script. Keep any activity that creates a transition for you — a before, middle, and an end where you’ve changed. You need that.

If you like imagining you’re in the same space that’s indicated in the script — fine, but the key is that you’re comfortable in the audition.

On set is different. The space is there.

It might not be completely real, so you can still let your imagination work. A set is usually quite realistic. It looks like the place indicated. An office looks like an office.

Exterior is even better. If the place is “the woods” and you’re in the woods, not much work is needed. Let the woods work on you and ease you.

A street is a street. On location is one of the joys of filmmaking for you as an actor as opposed to the theatre where it is never a real forest or street.

Greenscreen and motion capture you need to really imagine where you are.

“Where am I?” remains a key actor’s question. Is it a familiar place — your home or a new place? What memories do you have of this place? What images are created in your mind when you enter the new place?

The adage works here too . . .

It’s your space. Take your place.

Doors

Learn to appreciate the theatrical potency of doors.

Our Uta Hagen, when teaching away from her New York studio, always had the hosts install a stage door for her class.

Many things about doors.

Beginning, middle, end. Outside the door, different space, different thoughts, open the door, space changes, enter a new space, new vista, new thoughts.

Watch those actors who don’t give up the door so quickly. “Doorway acting.” Just like “acting with your back,” acting in a doorway has much to offer. Holding on to the door handle.

If your character is entering a room and crossing to a table, couch, or desk, explore what can be had to express your character’s wants and tactics by the speed and manner in which you open the door, cross the threshold, and close the door before beginning your trajectory.

Character is revealed.

The character alone in the scene anticipating another character’s entrance.

You entering the scene is dramatic enough. Keep your door open for possibilities.

The scene is the unit of work.

How do you work on a screenplay?

Breaking it down into its first big parts helps. Those parts are the scenes.

As actors, directors, writers, and producers, we work on scripts scene by scene. They’re the units of work.

You shoot scenes out of order, so you must work on each scene as a separate entity. Its own whole.

What are the features of a scene?

Beginning, middle, and end. Occupies its own time and space different from the other scenes. Can move the plot forward. Has its own event. Each character wants something specific. It, along with all the other scenes, makes up the whole play.

To call scenes the units of work helps define the idea that the one thing leads to the next. Or, step by step.

When you’re in that scene — that situation — you have to be fully there and nowhere else.

Within a scene, there are beats. Beats — as described by Stanislavski — are the next size of the play that can be worked on. The next smaller piece. There may only be one beat governing the whole scene, or a transition leading to a second beat.

In beats, characters talk about the same topic in similar tones, time, and space. That’s a beat.

Then there are lines, individual words, and punctuation. Smaller and smaller parts to be looked at. All of this makes up a scene, and all the scenes make up the screenplay.

It’s like building a house.

In episodic television, what happens in one scene does not necessarily make sense in relation to other scenes. Learn to play the truth of each scene and try not to get diverted by trying to follow an arc. There might not be one.

Episodic television really proves that the scene is the unit of work.

A read-through.

Some words are written to be read aloud, and some words are written to be acted.

When we say “Let’s read the scene,” we mean “Let’s play it, let’s speak it, let’s act it.”

Text is written in words, and you can get diverted when asked “to read” by thinking you’re reading and not speaking a character’s words.

A read-through actually means an act-through. Always. You’re an actor, not a reader. Other than at an event when you’ve been asked to read a statement, notice, or poem.

Patsy Rodenburg’s book is called The Actor Speaks.

“Just the facts, ma’am.”

This is what Sergeant Joe Friday, played by Jack Webb on the TV series Dragnet, used to say to witnesses when they strayed from the facts.

Getting the facts clear in a scene is half the battle.

Learn the plotline, sequence of events, key characters, location, time of day, good guy/bad guy, who’s lying and who’s telling the truth.

This is the foundation to knowing what you’re doing in a scene. Know the facts before you start Acting.

Then add the TV acting basics of being still, not blinking, and speaking on your voice.

Knowing your position or point of view is a different part of the work and is more sophisticated than knowing the facts.

Long before you get to anything remotely emotional in TV acting, you must know the facts.

That’ll keep your feet on the ground.

A great place to have them when you’re acting.

The event.

The event is what the 2nd AD writes in the call sheet for each scene.

For example:

“Josh nervously divulges his plan to the audience.”

“Dr. Hertzberg provides another breakthrough.”

“Lucy gets educated in finance.”

“Lucy and Josh find the picture in a drawer.”

These descriptions consist of a proper noun (the character), a verb (what he does), and the complement noun or subject — the recipient of the action.

The event describes the central action of the scene. It’s the main reason the writer wrote the scene. Sometimes it’s something new for the audience.

“Josh nervously divulges his plan to the audience.”

Josh may never have revealed his plan before, so that’s new to the audience and is a plot point.

“Lucy and Josh find the picture in a drawer.”

Maybe Lucy and Josh’s search for the picture was a MacGuffin and the finding of it a turning point in the story.

The event always tells you in simple terms the crux of the scene.

Knowing the event helps you to play the scene sharper.

Big scene.

That term can be a headache you learn early as an actor.

Not a useful phrase.

Yes, some scenes and speeches are long or more emotional or more important. But watch this idea doesn’t divert you.

Because it’s “big,” then you might want to push, work extra hard, be better because it’s . . . big.

Try not to do that.

Approach the scene as you would any scene — as a situation that needs to be learned.

The scene goes, as all scenes go, from one thing to the next. There is a beginning, a middle, and an end. You can use techniques such as “like” or “as if” to substitute your experiences for those of the character.

All the good prep work you usually do works here too.

The issue is not to be overwhelmed by the size or import of the speech or scene.

If you take it as a “big emotional scene,” you can make the common mistake of playing in a general wash of emotion indicating the gist of it.

You’ll be confused doing that. We’ll be confused watching it.

Go step by step.

All your work has common parts to it, and your methodology can be applied to all those common parts — even in different situations.

Stick with the reality of the scene — not the idea.

Sustain it.

When you’re shooting a scene, be careful not to pick an activity that is difficult to sustain.

It might seem authentic, creative, or cool at first, but after hours of repetition, it might prove unsupportable.

Eating lots in a dinner scene. Continuous coughing. Twitching your eye. Screaming. These have to be thought-out and well-practised to be done without harming yourself.

Jumping off a horse.

Maybe once, but for repeated takes, it’s the stunt person who has the technique.

Training with a professional coach prior to performing a role will enable you to learn new things. The spontaneous choice can lead to regret.

Many movie stars and series regulars don’t actually eat in meal scenes. By not eating, they can focus on the scene and not get diverted.

Think if you can sustain the activity you’ve chosen.

Lose it.

The phrase is apt as your character no longer has control of their conscious mind but, rather, has lost it. Lost that control.

As an actor, you need lots of good, open breath to play there. Straining your throat is an early mistake.

It’s like being blind.

Rage.

Once it’s all out, it ends. You can’t live at this extreme level for long.

As always in our acting, we don’t want to be acting in grey but in sharp, well-thought-out colours.

“General actor arguing” is grey.

What colour is the argument of your scene?

Essential oils.

The homework the actors had for the next class was size. Big emotion and big volume. Each were given events such as torture, birth, drowning, orgasm, trapped, eulogy.

They performed them well.

The work was excellent with good breathing supporting the vocal release of the emotion through the vowels. They had found their own truthful sources.

I then asked them to do more — cry more, suffer more, call louder — typical director’s result-oriented direction.

Most of them struggled with fulfilling the demand. I also got them to repeat the activity as if we were doing take after take. They struggled with that as well.

I encouraged them to use the pure source they had discovered through their sense memory work and add technique to that. To let their real emotion start and then make it bigger, louder, longer. Joining the technical with the pure can help fulfill the director’s needs.

A small concentrated impulse — like an essential oil — is enough to fuel size and repetition.

Technique coupled with the natural. A lifelong and complex pursuit.

As the actors tried it, we saw the relationship between organic emotion and technique.

The one thing leads to the next.

Follow how the scenes are built.

Something is happening, maybe a spy is lying, so you change your tack and pretend to retreat, drawing in our spy.

The one thing leading to the next.

The spy’s lying leads you to your switch.

See how the writer wrote the flow of the situation and how your character follows the movement.

It’s simple, isn’t it?

But key. Action to action. Beginning, middle, end, a new beginning.

Now you are backtracking, trying to lure our spy into giving over the information. Suddenly our spy reveals news, a secret that you didn’t know she had. Leading you on to something new.

Step by step.

Learn the simple progress of the scene. It may seem obvious, but the naturalness of how life unfolds — one thing leading to the next — is grounding.

You can’t add anything flowery on the scene until you have a solid base.

Learn the situation.

When preparing a scene, learn the situation — don’t memorize a scene.

Learning the situation allows your brain to assimilate the words as they are linked to what is happening in the scene.

Learning it is quite different from memorizing.

If you learn what is going on — how you’re getting what you want, the facts, relationship, time, place — you’ll have more to hold on to when you’re acting.

If you memorize it, you’ll probably just be holding on to the words. It’s not enough.

Always play the situation.

The situations in TV shows are iconic and usually each scene can be characterized simply. Such as girl flirts with boy, bad guy threatens, good guy speaks the truth, a couple argue passive-aggressively, two doctors do their job, etc.

Once you learn it as a situation — which it is — then you make it yours.

The language we use reflects our method.

Sharpen your approach and the naming of it. This isn’t semantics. It’s a question of clarifying what is your best practice.

The moment before.

This well-known practice can assist you to have a good start to the scene.

At best, it bulwarks against you beginning by reciting memorized lines rather than playing a situation. It is one of the best tools you can have as an actor to help you get in.

All scenes have a beginning, middle, and end — the beginning is the most important.

Given circumstance or backstory is different from the moment before, in that it covers more history, more time.

Time is key here.

An obvious example as how to use this precept is if you have a typical TV line like, “No, I didn’t see anyone.” Here you’re most likely answering someone’s question, which is not written as they “got in late” in the scene. So, you could write out the imagined question “Did you see anyone?” as your moment before. Having that moment before imagined will allow you to have a start from a useful place — your imagination.

And it brings your breath into play — another key element. By “hearing” the question after “Action!” you will breathe in to answer with your first line.

It’s on that inhalation that you drop in.

Your imagined, unwritten question sends a signal, which creates an impulse in you and your breath as needed and respond.

Send and receive — Yale School of Drama.

You create your own send and receive. You start from your imagination. You engage your breath.

There are many ways you could use the moment before depending on what you like and the scene. Could be a headache — feel the headache; coughing; out of breath; lost in thought; nervous and more. Something psychological or physical or both together.

Start there, breathe that in, and play.

You could be in mid-activity with a prop.

Launching from your moment before is qualitatively different from being pushed into their time and space on action and then trying to catch up to get into yours.

Practise to develop a habit to begin your way.

Think quickly.

One of the best directing notes I ever received was from Peter Bogdanovich who said to me, “Think quickly.”

I’ve repeated that to many actors since.

It doesn’t mean speaking quickly. It means moving forward doing what you need to do in the scene and eliminating the actor resets.

You jump off the cliff instead of inching over the edge — carefully.

You may be acting this way: dialogue — actor’s thought; dialogue — actor’s thought; dialogue — actor’s thought. Constantly interrupting yourself.

Resetting and dropping out.

It’s leaving behind all and any preparation you’ve made. If you try it — thinking quickly — you’ll be surprised how much guiding and checking you were doing. Giving that up creates space, and that space leaves you with nothing to do but play.

Be careful with the word quickly — it doesn’t mean fast.

The time, speed, pace of your mind in the scene and that of the scene itself remains intact and is found in rehearsal and shooting. It’s neither quick nor slow. It has its own integrity.

The time in your mind and that of the scene is the time needed.

“Pick up your cues!” is something directors and teachers say. Watch you don’t give up your time in answer to their direction.

John Barton, in Playing Shakespeare, uses the same phrase — think quickly.

Three basic levels of arguing.

There are as many levels of argument as there are human situations. Here are three common ones.

Passive-aggressive.

This common low-level argument form is frequent in relationship and sentimental TV fare.

Distinctive characteristics are the level, tone, and repeated beginning, middle, and end structure. As is often the case, the dialogue is call and answer as each character speaks nearly the same amount of words and syllables as the other.

There is a ping-pong equality to it.

The ping-pong analogy would be played something like this: Hit, hit (aggressive); put the ball down (passive). Repeat: hit, hit — put the ball down.

It’s the deliberate and fake putting the ball down that gives the passive quality. “I’m not arguing anymore. I’m above that.”

You want to argue (aggressive), but you pretend you’re not, so you end it. You put the ball down. You do it with passive bridge phrases like “Anyways.” “Whatever.” “Forget it.”

Then you start again — hit, hit.

Your burning need to win won’t let you stop.

Argument.

This is when you’re in full, normal argument state. Blood is up, voice is connected, and you’re committed to argue it out. You don’t drop the ball or go back. It ends either by someone leaving or with a final clinching point.

Again, as in all beats, the two sing the same song. The rhythm, tone, volume, length of line all echo each other and your agreement that you are arguing. You make agreements with your partner, and they are usually unspoken but absolutely clear.

This middle level of argument will not end in divorce or death. Part of the overall agreement at this level is that the two characters will continue their relationship. An apology may or may not be made afterwards.

Lovers have the right to say anything to each other in the heat of the moment.

Lose it.

The phrase is apt as your character no longer has control of their conscious mind but, rather, has lost it. Lost that control.

The argument now becomes more physical than mental. The pure emotion, the energy, the heightened breathing are all physical forces fuelling the size of the argument and the content.

This argument can lead to divorce, death, or any kind of violence. Uncontrolled acts.

As an actor, you need lots of good, open breath to play here. Straining your throat is an early mistake.

Losing it is like being blind.

Rage.

Once it’s all out, it ends. You can’t live at this extreme level for long.

As always in your acting, you don’t want to be acting in grey, but in sharp, well-thought-out colours. General “actor’s arguing” is grey.

What level is the argument of your scene?

From “Ha!” to “Help!”

Your character is a low-status bad guy. You’re confronted by a high-status good guy or cool bad guy.

There can be different responses from you, the loser. Here’s an iconic order.

Laugh it off.

The cool guy demands payment on the loan or else.

“Ha!” You make a joke, crack wise, laugh off the threat. First tactic.

He pulls out a gun. Stakes are raised. Tactic failed.

New tactic.

The high road.

You claim your right to be left alone and protest their nefarious threats. “How dare you?” You take the high road.

He smacks you across the face. Stakes are raised. Tactic failed.

New tactic.

I’ll tell.

You threaten legal action. “If the police find out . . .”

He shoots you in the leg. Stakes are raised. Tactic failed.

New tactic.

Sorry.

You apologize. “Please, I’m sorry!”

He shoots your partner dead. Stakes are raised. Tactic failed.

New tactic.

Oh God.

“Help!” You beg on your knees and cry for mercy.

Typically, they take the money, shoot you, or both. End scene.

Tactic failed.

We see this laugh-to-God iconic journey repeated in Hollywood movies. The three neophytes in Pulp Fiction follow that journey when the hitmen come to collect the money.

No icing.

If you’re asked to bake a cake, just do that.

Don’t add any icing.

Your direction is to walk across the stage. Just do that. Don’t add. De Niro says it’s the most important thing and the most difficult.

Use your observation — one of the pillars of acting — to see how you do the simplest things. Observe others doing the simplest things.

Human behaviour.

That is practice you can do when not in class. Take that up seriously. Professionally.

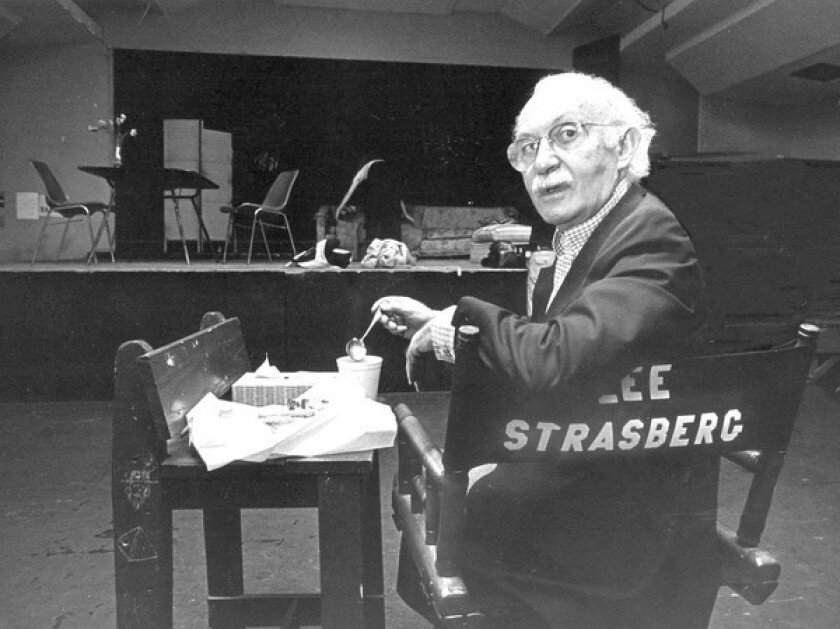

There is a story — perhaps apocryphal — that Lee Strasberg said the only actor he ever saw walk across the stage the way a human being walks was Eleonora Duse.

Maybe he did, and maybe she did. Point is, we like the story because it exemplifies the importance of simplicity and truth.

Be sharp with yourself in how you do this work.

Part of what makes it difficult is that it isn’t dramatic. No screaming, crying, fighting. No pages of dialogue, complicated blocking, greenscreen acting. So, it can deceive you in its simplicity.

It might seem boring.

To cite another great actor, Uta Hagen always had a scene study door wherever she taught. For her, entering was a decisive moment. Again, so simple and obvious, but on examination and practice loaded with importance and potential.

She stressed the qualitative difference between being outside the door and entering and seeing the other person. Just that act.

When the cake is baked well, it’s very tasty.

Pick a page, any page.

There are many wonderful writers on acting: Stanislavski, Sanford Meisner, Lee Strasberg, Keith Johnstone, Uta Hagen, Harold Clurman, and others.

When you want to be inspired and enlightened, pick up one of their books and open it anywhere.

Read until you get bored and then put it back on the shelf.

These best books on acting can be read cover to cover, but be careful you aren’t trying to learn how to act by doing that.

The ideas in these books will support your practice and experience that you have had as an actor. The experience comes first and is most important; the ideas follow and support that experience.

These classic texts can be picked up and opened anywhere and the passage will usually be interesting.

Occasionally you’ll find you want to read one of them from cover to cover. Wonderful. Terrific.

But don’t try to remember or learn anything from what you’ve read. As a working actor, you’ve had your experience, and when an idea written in one of these books speaks to you — it will. Use these books in the same way you do your best practice. When and how you want.

At other times, you may need to solve a particular acting issue at which point you can turn to a section in the book and read what the author has to say on it.

It’s very useful to apply theory to a detailed point of work that you’re actively taking up. The book may give practical tips or a methodology that you can immediately put to the test.

If you’re seeking light, clarity, or good energy, these books can provide it.

Pick a page, any page.

Playing potential.

In auditions, develop your ability to see parts of the scene that have potential for you to play. Particular and specific moments of playing. Moments that are describable and definable.

At first glance, something in a scene may appear problematic, but upon examination, you can see it as potential.

If the script calls for you to fire a gun and that might seem like a problem, explore its potential.

Are you a professional killer? Are you firing in self-defence? What is your emotion before firing and then after firing. Exploring the moment gives you food for your acting and lessens the worry about “how to do it.”

You don’t need a prop gun. You can use your hand and point your finger. It’s your acting of the moment that they will be watching, not the gun.

Firing a gun offers a great transition.

If the script calls for you to vomit, that can seem impossible to do in an audition.

Again, explore what is making you sick. Are you trying not to throw up? Are you pregnant? Are you drunk? Make whatever sounds you want during the vomiting. You won’t be judged on that, and nothing has to come out of your mouth.

Then how do you feel afterwards? Another great transition that can get your imagination going.

The problem has turned into potential.

How to film these kinds of moments on set will be solved with you, the director, and any specialists needed.

Help or hinder the lead.

Does your character help or hinder the lead?

If a character played by a leading actor, such as Harrison Ford, is seeking to get on a plane so he can rescue his daughter from threatened death, then the character playing the ticket agent must either be helping the Ford character get on the plane or blocking him from getting on.

Certain roles can be categorized as either helping or hindering the lead.

Next time you get a script, ask yourself that question. It’s a small, important point to clarify.

If there is no space on the plane and Ford is demanding, cajoling, or threatening to get on the plane and you’re the ticket agent saying, “There are no seats left,” your role is crucial. You are the obstacle for him to overcome.

If, on the other hand, there are no seats on the plane, but you devise a way to get him on, then you become equally important. An important helper.

In one scenario you hinder, and in the other you help. Both roles are day players — and crucial.

You really do support the lead when you fulfill your job as written in the movie. That’s why they are called supporting roles.

The Harrison Fords appreciate it.

Foil acting.

There’s a term.

You have an audition for a part in a series. The trope of the series is that there are dead people who can communicate with living people.

There is a set of leading roles all fulfilling this particular genre.

One lead character needs parents. The parent’s job is to show certain aspects of the lead character that help drive the plot.

The parents are a foil.

An excellent example of a movie star being the foil to allow another movie star to take their space is in the movie Roman J. Israel, Esq. Colin Farrell knows he is a foil to the complex and unconventional role that Denzel Washington plays. Farrell astutely keeps still, fills the picture of a corporate lawyer, and leaves Washington to do all the fancy footwork.

Merriam-Webster defines a foil as “Someone or something that serves as a contrast to another.”

The writers want to make a point about the main character and need a foil to contrast and show something specific about them.

Learning how TV and movies are written including tropes, icons, clichés, reveals, and more can help you play more specifically. Can help you fulfill your job in a show.

Not being sure why your character is in the script or — worse — thinking it’s more than what it is can cause confusion.

Find out what the thing is and not what you think it is.

Or you might get foiled.

Language.

As an actor, you already know much about language.

And tomes upon tomes have been written about it. Let’s touch on a few points.

Writers know language best and actors second best. They create — you interpret. You always begin with the written word. Text.

In TV, the writing style reflects the genre. Learn those clues to better deliver what is needed. Shows with speeches having three lines or more and clauses in the line or shows with one-line speeches and single-syllable words. Different.

The length of line, the number of syllables give the music of the show. The shorter lines require less breath indicating character, action, and genre. More breath for longer speeches, and complex words indicate different character, action, and genre.

Verbs. Doing your prep, mark the verbs.

Nouns. Is the point of the line driving to the noun? Nouns are the facts of the scene.

Adjectives. Observe if you’re emphasizing the modifier or the noun.

Bridge phrases — like, anyways, so, well, listen — transitioning from one point to the next. Changing the subject, giving you status as you control the scene. They give your brain time to formulate the new. It stops or diverts the other character and gives you the floor, the status, the control.

But. This wonderfully useful word juxtaposes the previous point and introduces your new one. Poses the opposite. Contradicts. From the B of but to the T of but can really make a point. The T is a good sharp sound.

Punctuation. Even in postmodern TV series, punctuation is still the guide. Old rules still stand: period is the end of the point, allowing you to go to the next point. Beginning, middle, end.

Vowels carry the emotion, consonants the intellect.

The English emphasize the noun and not the adjective; the Americans tend to hit the adjective, the modifier.

Text analysis is practical, not academic.

Hamlet says, “Speak the speech, I pray you . . .”

How your mind enjoys its own cleverness with language.

As you speak, your mind can be aware of the beauty and clarity of the language it’s creating.

With certain characters — speakers — there is an awareness that their dialogue, their speech is good. Or the manner in which they are delivering it sounds good.

It’s an overlapping support, praise, and confidence-boosting ride.

You speak; it’s beautiful; you’re encouraged to speak more; it’s better; you keep speaking; and so forth. Your mind likes it, and you like your mind liking it.

Think of Mark Antony in Julius Caesar and how his brain would be processing as he moved forward in his funeral speech. He would have liked it as he began the repetition of “All honourable men” and “Ambition.” He would know that it was making the point in an artistic way and very moving orally.

As the speech moves forward, one voice in his brain could be saying, “It’s going well,” “I like this,” “They like it.” Giving Antony more strength and confidence to continue and widen the parameters of his speech.

Observe when you have text that is tasty.

Some actors have the awareness that they speak well.

Donald Sutherland was a speaker. An actor who enjoyed the enunciation, the sound, the variety, and the complexity of language. Often, it was one of his character’s main qualities.

Call it what you will — a showing off, a celebration of English, the beauty of rhythm, syntax and colloquialism — a love of language.

The minting (John Barton’s word) of language as you speak, and your awareness and enjoyment of that minting are gold.

Learn to enjoy the sound of your own voice.

Counting words.

Does counting the number of words in your line and the number in the other character’s line help you learn the scene?

Part of the form of the scene.

Supporting the content.

Often the two lines are equal. Rhythmic ping-pong. Back and forth. Echoing each other.

Either in agreement — or not.

And then there’s syncopation. When the speeches of each character differ in length, composition, and word type. A five-line speech followed by a one-line answer. Unequal.

The form revealing relationship, status, intent, etc.

While working the Kaffee-Ross scene from Aaron Sorkin’s A Few Good Men in class, we discovered that the scene ended with a couplet. Both lines with equal words and syllables; both saying the same thing.

“Oh, ya? Well, blah, blah, blah.” And the response “Oh, ya?! Blah blah blah to you too!”

Same meaning, same number of sounds, same single-syllable words. Couplet endings.

Equals speaking equal language.

Sorkin knew what he wrote.

You act in English, and these musical rhythms are part of that language you speak. Text expressed in repeated forms to elicit particular meanings. Content in the form of content.

Count the words.

“Can I change the words?”

It’s a bit like how many fairies on a pin head.

Much debated by actors in bars.

There is no one answer to the question, but even if there was — what good would that do you?

Treat each situation as needed and as dictated.

For a typical TV audition where a particular tone is needed, a particular type of role, then focus on that. The words can be secondary.

If there are medical, military, or legal terms, these must be exact. Part of that reason is to show the producers you can handle that language.

Some projects demand lots of improvisation, and others are letter perfect. You adjust and do your job. As a professional, you fulfill the director’s vision.

As far as casting goes, they don’t check you word for word, but rather want to see if you suit the role, look right, and have caught a colour that suits the episode.

In acting class, try working letter perfect for a while. See how that suits you. Then try only knowing the gist and saying it mostly in your own words. See how that goes.

Don’t get sidetracked by watching interviews with movie stars saying how they improvised every line and then think, “Ha, that’s the answer!”

Big movie stars can change the text to suit themselves. And sometimes they can’t.

Student films, web series, short films, low-budget features are generally all open to changing the lines.

Focus on playing the situation truthfully and simply as you — they’ll let you know about the dialogue.

Point.

As you rehearse, add the word point to the end of a line.

Better still, say it at the end of each point you are making, which may be more than one per line.

Say it with the same tone, intent, and volume as you’re saying the line.

It gives you a magic opportunity to send the point of the line farther. And as you do it, your brain is realizing in reverse what the point really is. It’s a way for you to clarify your intention and give your brain a nice, sharp workout.

It’s a good way point, to sharpen your work point, because as you say it point, it pricks your point point, into a brighter clarity of intent point.

It goes like that.

Drowning.

In an audition class one evening, there was a scene where an actor had to drown.

How to do it? She was stumped. Maybe we all were.

We thought we’d improvise drowning and see what it revealed.

Revelatory.

First it came out there were two parts to it — above water and below water. That meant breathing (above water) and holding your breath (below water).

Well, as an actor, you know anything with breath as key is very useful to you. Something you know and like a lot.

She did the drowning improv a few times, and each time the discovery was the terrifying experience of not being able to breath versus being able to.

Essence of life opposites.

When she was submerged, the whole class was holding its breath and a wave of fear swept across the room. I was clutching my chest, fearful, wondering, hoping.

Then! when she broke the surface and gasped, we all gasped. It was powerful. And all sourced from the breathing.

I haven’t done that in class as an exercise since, but I will.

She went back to the audition format and did the scene again. She found that if she kept that essence of not breathing/breathing and maybe did it three times where the drowning part happened, that answered the question “How do I act drowning?”

Mean it.

That means you mean it.

The you is understood. It is a very useful reminder phrase to keep you playing truthfully. It is simple and direct and with the you understood, it can keep you on the hook and not off it.

Try using these simple guide phrases and see if they assist you. Just before they call “Action,” you can say, “I’m going to mean it.” Or after a scene, you can ask yourself, “Did I mean that?”

You have to practise something — including a simple technique like this — seriously for a period of time before you can tell if it assists you; otherwise it’s an opinion and not based on your experience.

Observe yourself in life when you really mean something, and feel where that comes from. Observe the difference between meaning it in life and acting it in a scene.

As James Cagney said, “Hit your mark, look the other fellow in the eye, and mean what you say.”

Don’t act it — mean it.

Between the lines.

Those little thoughts that occur as you’re ending one line and beginning the next one.

You’re speaking your line and your mind is conjuring the points and clarifying the points that you want to make and once your mind is happy and sees that the point is about to be made, that is when your mind begins to create the next point. It’s that time that is interesting and useful to observe.

Your mind, happy with what it has created, now begins building a bridge to the next line. From thought to thought, line to line.

It happens so quickly as the brain works at such speed that we often don’t pay attention to it. That moment of creation.

But that moment, which is both the conscious and the subconscious mind working, is useful to observe.

Sometimes as you’re finishing your thought — your line — the mind says that’s it, there’s no more, and I’m done. No new speech created.

Learn to observe this transition — that bridge from the ending of one idea or thought to the making and beginning of a new one. A new line.

It’s a fabricating, a conjuring, a minting, and it happens in the space between the lines.

Beginning, middle, end.

In acting class, working with two beginners, one of them asked, “How do you do commercial auditions?”

One key part is to go ready to improvise the situations they give you.

Another part is to find the beginning, middle, and end of the scene.

I made up a Coca-Cola ad. The directions were:

You walk in very hot and tired; you wipe your brow; look down at the table and see a can of ice-cold Coke; you pull the tab and drink; then you make a satisfied sound, “Ahhh!”

They both tried it. They missed the transitions and thus the parts of the scene.

I said there are beginnings, middles, and ends to this scenario. As there are in all scenes, all things.

Let’s look at it.

The walk starts. Beginning. The walk continues. Middle. The walk ends. End.

Wipe your brow. Start wiping. Begin. Continue wiping. Middle. Finish wiping. End. (They asked what started the wiping but couldn’t see that it was the impulse from the sweat. The sweat on the brow sends the impulse to the brain, which kicks in the arm mechanism to wipe the forehead. All happening at the speed the brain operates.)

Thirst sparks the impulse to drink. See the Coke. Beginning. Snap the tab and drink. Middle. “Ahhh!” End.

I had the actors do each part and say out loud “Beginning, middle, end” as they did it.

It was crystal clear to see how impulses fire the brain into activity. We saw it in a slowed-down and highlighted way as the actors said “Beginning, middle, end.”

You can’t begin until you’ve ended.

You’ve finished the beginning of this entry. You’ve read the middle and now

. . . the end.

Drone phrase.

Find a phrase that is a key to what you’re playing.

Use words and phrases that you like and use every day.

“You’re stupid.” “Idiot.” “You’re scared.” “I like you.” “Nice eyes.” “I’m winning.” “You’re losing.” “Please.” “I’m sorry.”

Swearing. Anything simple that you can repeat at any time during your text or your partner’s text. It’s an exercise suited to acting class.

And useful to find on your own in your prep.

Phrases that epitomize your actions, your tactics, what you want, what you think of the other character, etc.

You speak your text and at the same time speak this inner monologue line — at any time. At first, it will seem disconnected and mechanical, but as you practise it, the phrase becomes part of the flow and supports the actual written text.

Say it a lot at the beginning so you get used to it.

Once you’ve assimilated the drone phrase, it’ll run through you as you play, supporting your work.

They should be short and sharp phrases that can make you smile with identification as to what your actions are in the scene.

It’s a hyper exercise. Part of unconscious creativity. Let the idea in the phrase float with your conscious, real-time acting.

Releasing the inner to support the outer.

Taking notes.

I often say to the actors, “Write this down.”

What I mean by that is — take note of it.

The comment can also be taken literally if you have a notebook.

Writing notes is one of the ways you learn. As you watch and listen, your mind is deciding what to write down. You’ll write what you like the most.

You can make up your own notebook format with highlights, boxes, ticks, underlines, colours. However your mind organizes it.

You don’t have to hand in your notebook to get marked after acting class.

If you make it your habit, you’ll start noting things from watching films and plays, from listening to interviews, from reading articles and books, listening to podcasts and watching videos.

An actor’s notebook is different from a diary.

If you do it over your life’s career, you end with an interesting compendium of comments, observations, quotes, summations, and zingers. As the years go by, you may find it interesting to go back and read early entries.

You’ll have a kind of noted history of your acting life. You’ll see if what you thought important then you still think important now.

You get better as an actor by doing — the notes will support your practice.

(Always put down the date in your entries — at least the year!)

Left to right.

To get the left in a scene, you have to go right.

Or black to white.

Often, you might disregard the importance of the beginning of a scene waiting for the big moment to then start acting.

The moment when the news is given.

“I stole the money.” “I killed the girl.” “I’m leaving.”

The key to receiving that news — the event — or giving it is to be fully into the beat before it. I call it “making spaghetti.”

Cook, cook, cook; you’re only giving the other character 20 percent of your attention; the two of you are talking back and forth about normal things; the spaghetti is cooking; then the news — Bang! 100 percent attention. The spaghetti cooking stops.

Swinging from left to right.

If you’re languishing in the middle — waiting for the big moment — you will not receive the news fully or deliver it well.

The further and sharper you go in the opposite direction to a big moment, the more difficult the transition. That gives you more to play.

The obstacle of dealing with the new.

More emotionally.

Sometimes, in class, I get the actors to literally lean to the left and when there is a transition, they lean to the right. The farther, the better.

You want to create active volition going from one state of mind to another. Watching you deal with that messiness is what is interesting.

A balloon.

At the National Theatre School of Canada around 1970, the director John Hirsch made a speech to the students.

In his speech, talking about the shaping and pacing of a play and the actor’s role in that, he used the analogy of a balloon.

He said one had to be aware of how much air they were taking out of the balloon.

At certain points in the play, scene, or speech, only a small amount of air should be let out. At other points, more air.

To let out too much air and deflate the balloon at the wrong time is the error to avoid. Too much air too soon, leaving none left.

While preparing an audition recently, I reflected on the job my character was there to do in the episode of the TV series. I had started off taking too much air out of the balloon.

I considered why the writers had written that character and how the device of this character served the story.

That informed me to lessen the amount of air I was taking.

When we take the right amount of air out of the balloon in each line, speech, and scene, the balloon empties naturally.

Leaving the audience happy to watch as it deflates — from full to empty.

(In 1965, Hirsch, founder of the Manitoba Theatre Centre, directed the landmark production of Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage starring Zoe Caldwell.)

An arrow.

When you send a line, it can be like sending an arrow.

You could send that arrow right through the other character and out the other side into a wall ten feet behind.

Or you could send the arrow just to their chest, letting it stick there . . . hurting.

The arrow could fall well short.

How do you draw back the bow? Rapidly, or slowly and deliberately? Is it your first time shooting an arrow? Are you a professional or a civilian? Are you defending yourself or attacking to conquer?

What tip do you have on the arrow? Is it poisoned, an ancient stone tip, high-grade steel, thin and razor-sharp, serrated?

You must play sharply. That’s how we live — like a series of very specific arrows shot from very definite bows.

See it. See what you mean, want, and how you send it — your line of text.

“I go, I go; look how I go. Swifter than an arrow from the Tartar’s bow.”

Follow.

When you’re playing a scene, consider if you want to lead (drive the scene), stay with your partner (equal), or follow.

To follow is to be active. But you lie back. Like a lion.

Very quick of mind but following. It’s deceptive. It’s lighter.

It’s not slow and heavy, no — it’s a different energy than leading. Having to drive a scene might put unwanted pressure on you while following might open space for you.

There are different concepts to playing a scene, different techniques that can be useful.

You can sometimes “quick cue” the other actor, cut the space between your lines and theirs, mentally being on top of their lines — ahead of them.

Following can be thought of as on the back foot and quick cue on the front.

You can also “slow cue” someone, which is a little different from following. You’re not late on your cue; you just stretch time a little, slow it down. Leading a line with an “uh” can fulfill that.

Look for crafty, sly, and clever concepts to playing scenes. Methods of attack that you like and may not have learned in drama school.

Try them.

Do nothing.

After coaching an actor for a time, I often put them on the “Do nothing program.”

It can be successful.

What does it mean?

It doesn’t mean to do nothing. It means do something different. Usually the actor is working too hard. Which actually means not working well.

All big concepts.

Simply put, I’d say, “Look, for this next round of classes, get the scene, look at it, and don’t do any of the prep work you would normally do and don’t memorize the words. Just get the gist, the sense of it. Then leave it. Give it space.”

That immediately puts the actor at ease. It rests their weary mind.

But, as in life, they immediately wonder, “What the hell will I do?” They should let their mind ramble and all the usual questions can come up, but don’t act on them. Basic psychotherapy. The very act of the rest, the change, the do nothing, will have an effect.

Don’t try to catch and hold on to that experience. Just have it.

Then when you come to class, you’ll play the situation — the scene. As a trained and experienced actor, you’ll get lots of images and ideas as soon as you read the scene. What the scene is and what your character is doing.

That’s enough to practise with in class. It can even be enough to shoot on set.

You can see that the do nothing program is actually doing something. You will act the scene.

Best is to pick something simple to do with your partner. Any small thing that hits you coming from who your partner is and from where you are. An impulse. If you can go with that, then the Do nothing program is really functioning.

Very little prep. Immediate choice.

The program isn’t guaranteed — but it is tried and true. You can see almost immediately how much more open the actor’s face is and how much simpler their work is.

Watchable.

It’s a pause, isn’t it?

Say nothing.

Say nothing is when you change your self-talk.

Your old narratives.

It’s a cousin to the Do nothing program.

It’s essential for growth to look at your narratives.

You know, like the one you learned as a young girl that Uncle Nate was a heavy gambler. That’s known. Then one day, many years later, you actually look into your uncle’s life and find out he only gambled for a few years to pay his way through college.

That narrative gets changed. The reality emerges.

You can develop many during your early years acting. “I can’t cry.” “My eyes are too small for film.” “My voice is squeaky.” “Theatre is big; film is small.”

Actors who come to my class with mostly a theatre background often repeat their narrative of “I can’t act in film because I’m a theatre actor.”

After hearing this repeated a few times, I encourage them to change their self-talk. Just don’t say it anymore — and you can’t say it in my class!

You’ll still think it, but don’t say it. Basic psychotherapy.

That has a positive effect on your consciousness. On your mind. If you do that — stop saying the narrative — the idea dies down. Speaking it out loud fuels it.

Old narratives are like old friends even if they are poisonous. We know them and in a funny way are loathe to give them up. That means you may and probably will keep thinking those thoughts, but the issue is to not say them and not to act on them.

That’s change. It’s essential as you become more professional that you examine old ideas and see if they still stand up. See if they’re true.

Change happens in small parts.

The theatre actor just keeps practising acting for camera but drops the narrative.

Raising your bar in part means to stop whining (whinging, as the Irish say) about things you’ve been whining about for years.

Even if everyone else still whines about them.

Inner monologue.

Literal or subconscious?

You can use your imagination to develop a like inner monologue that your character could have. That’s useful work.

You develop aspects of your character — speech, physical — and you make up an inner monologue. Sometimes you let that run while you play the scene.

That’s the most common inner monologue work.

It hit me that we seldom choose a thought from our own subconscious.

And best would be something the moment you’re about to begin the scene. “Geez, I’m tired.” “This actress is bugging the hell out of me.” “Man, this actor–movie star is so centred.” “I’m nervous as hell.” “Cool, man, I feel cool as ice.” “Love the sound of my voice.” “This is fun.”

Choosing an inner monologue like one of those could be useful, interesting, and odd.

Helps throw you off—always a good way to get on.

Which we love.

Caine and able.

Michael Caine is a wonderful actor.

And he was a movie star.

The 1987 Michael Caine on Acting in Film, Arts, and Entertainment video is interesting to watch.

I took two tips from his video.

First, carry mints or breath spray so you have fresh breath when acting. Whether you’re kissing or shouting at your scene partner, it makes a difference and is courteous and professional.

And second, in your close-up when looking at the off-screen actor, look in their eye closest to the camera. It has a big effect on how we see your eyes.

Follow Caine’s two tips to be a more able actor.

Snap!

While working on a scene in class, the actors weren’t being sharp enough in the conjuring of new ideas and the receiving of them.

The scene, from the movie Johnny Suede, has one character coming up with topics on a pro and con list.

Neither the actor coming up with the idea nor the actor receiving the idea were realistic enough in their sending and receiving.

Colleagues at the Yale School of Drama shared the idea with me of “send and receive” as one way to describe human interaction.

In class, I said to the actors: “Let’s try a new exercise and we’ll call it Snap! As soon as you send the new idea, snap your fingers and point, and as soon as you receive the idea, snap your fingers and point back.”

They did it. They liked it.

It highlighted the send-receive play.

We then began to elaborate on the question of receiving and noted that you can receive at different speeds. Sometimes you get the point before the other actor is finished speaking. Sometimes it takes time before the penny drops.

It’s definitely not always at the end of the other actor’s line.

The same with sending.

We send with all different levels of intent.

When you receive the sent point, you react with an impulse that feeds breath so you can speak in response. Sometimes you breathe, sometimes you speak, sometimes you just receive and the impulse doesn’t trigger breath or speech.

You can look up how fast the human brain works — it’s useful to know.

As the instrument you play is you, then the more specifically you observe how you function, the more that can serve your work.

To the close-up.

They say the close-up is the money shot.

In television, it certainly is the size we see most. Talking heads, they call it.

Learn to use the time of rehearsal, blocking, master and medium shots to choose what you’ll do in the close-up.

Note where an emotional connection produces a move that will play well in the tight shot. A move, a tilt of the head, a glance that makes your point. You’ll learn there’s enough time prior to the close-up to get yourself ready for it.

Realize that they won’t use much of the master or medium sizes. Those setups are good rehearsal time.

You don’t want to be surprised when the close-up comes.

Triangles.

In your close-up, as you think and speak, your head movement can follow a triangular pattern.

It looks good onscreen.

And it’s part of film language. We recognize the pattern of the movement from movies, and it usually indicates searching for an idea, getting the idea, and then finishing the thought.

It’s also recognizable human behaviour.

In life, we make the same triangular movement, so it’s both truthful and technically sharp — meaning it suits the frame and life.

Can’t get any better than that.

It can go like this: the other actor sends you a line, and as you receive it, your head dips down and to the left as you’re thinking of your response. Then as your thoughts clarify and words unfold, your head comes up on the left. Finally, as you complete your thought, your head returns to its starting position on the right looking back at your scene partner.

It’s a flowing triangular movement based on your thought and dialogue.

It goes from right, down, up on the left, and then back again on the right.

It could go from left to right.

It’s what you do when you think. You can’t hold eye contact and find your thoughts, so you look away. Once you’ve got the complete thought, you can make eye contact.

Certain high-status characters are trained to think and keep eye contact. To not give away a tell. So they can receive, think, and respond without looking away.

Triangles aren’t a rule or something to do mechanically, but it’s a movement pattern that humans do and looks good onscreen.

Knowing that something looks good on camera quiets the doubt.

How to watch your footage.

This is tricky.

You’ve got to be professional and use that as your guide.

Meaning don’t watch it with your partner, friends, family, or even most of your actor colleagues. They aren’t professionals.

Cherish your work; guard it. It’s hard fought for and precious. Treat it as such.

It’s not for giggling, Ooh-ings, Wow-ings, or Amazing-ings. It’s for critical study to get better at acting.

If you’re self-conscious at all — stop watching. If you don’t like your eyes, lips, nose, or the sound of your voice — stop watching. This is important.

If it’s a negative experience, then it’s a negative experience. It’s got to be positive and informative.

Did you hit the right note, is your mask suitable, did you catch the transition, is it believable, can you see yourself, can others see you, is it simple and clear, did you do the job required in the movie?

Ask practical questions about what you see. Ask specific questions about what you see. General “I hate its” or “I love its” aren’t useful.

Play it with just the sound. Listen to the tone. Play it with just the picture. Watch your movements.

You can watch it with professionals who’ll give you objective critiques. That’s useful.

And just because everyone watches their footage doesn’t mean you have to.

Always an actor in front of you.

Whether acting in an audition, on set, or in class, a real person is always in front of you.

So, there’s no need to pretend.

Try to catch their attention.

Really try.

It won’t be easy to attract the attention of a famous actor; in an audition, the reader will usually have their head down, so getting them to lift their eyes will be a challenge; your fellow actor in a scene might be nervous and have “the Plexi’s up” (eyes glazed over, locked in position looking like Plexiglas).

Your fight to reach any actor in front of you is immediate.

Can you get the other actor to blink, blush, smile, hesitate, or give a tell as you send your line? What is there about the other actor that you like, and more importantly what is there about them that you don’t like?

The difficulty in trying to reach the actual person in front of you is everything — puts you right where you want to be — in the hot seat.

The camera loves that.

Everything is in the detail.

An old and useful adage.

See how applying it helps put you in.

If you’re playing a character who is an investigator, look at the prop you’re holding and find the tiniest part of it. Go from that part to the next one. Small steps.

Can you feel your mind calming? The audience likes you calm.

Detail does mean specific. Detail does mean simple.

If your character is in a scene with big themes of life and death, it will be through the small — the detail — that you’ll get to the big. Reaching for the huge, theme may overwhelm you and have you indicating to try to show it.

Details in the text, the speech, the line, the word, the letters in the word.

Staying with the detail keeps you on your feet and in your time. You can’t get ahead of yourself if you go step by step. Nor can you fall behind.

What you wear in the role. Your collar: laid flat, pulled out, half turned up, all the way up, tips pointed. That kind of detail helps you create the role.

“The devil is in the details.”

Make trouble for yourself.

Find moments in the scene when you have to struggle.

To fight.

There might be a place where you are only giving your partner 50% of your attention. When she gives you the news, you’ll be jerked to 100% attention. You’ll be caught off guard.

That’s useful.

To you as a player — having to struggle on the spot. And for the audience — who loves to see a character trying to overcome an obstacle.

Learn to find those moments in scenes. They’re gold.

“Life is messy.” That’s the watchword. Find moments when you are in the “mess.” Best messy moments are like those that you yourself get into.

Maybe there’s a place where it’s easy. You’re dreaming, having a peaceful time of it. Then more news — the event — hits you and you fight to regain your balance.

Good.

You may or may not let your partner see you getting hit with the news. See you fighting to regain your balance.

Sometimes the simple act of trying to remember complicated text can be the “trouble.” Or remembering the blocking.

You’re trying to put yourself on the hook, not get off the hook.

Look for trouble.

Transitions.

It can be called a “moment” or a “beat change.”

Paying close attention to transitions in your scenes can help you play sharper.

Transitions: that time and space between the end of a beat and the beginning of a new one, where either your mind or the other character’s mind leaves the current subject and starts a new one.

The transition is often caused by one character revealing something new.

A change.

That change of breath for you, that time where you either float, leap, or are pushed to the new is so full of life, waiting to be tapped.

The transitions are filled with seasoning for the next chunk of dialogue. They flavour it.

They are often marked by physical activity such as standing, moving, or turning your head.

Your action verb usually changes after the transition.

In the early days, you might just memorize lines and because they are typed in order, one after the other, you give them equal importance. That can lose you the potential of the transitions.

The writers write the text as the character’s mind thinks and speaks it. Unequally.

A transition is often spontaneous, organic, and unconscious.

Pitfalls with transitions: you plan it and it lacks the idiosyncrasy of real life; you go the other way and it is flat; you telegraph it.

Learning and knowing the parts of a scene make them easier and clearer to play. Once you’ve identified what it is, all that’s left to do is to do it.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines transition as “a change or shift from one state, subject, place, etc. to another.”

Your mother.

There’s a limit to what you would let someone say about your mother.

No way will you allow your mother to be humiliated beyond a line of acceptable social humour or criticism.

We defend our mothers.

This is a vivid tool when you’re asking the question “What’s this situation like?” It could be like when you need to defend your mother.

Like the way you defend your characters. How they’re always right and believe — for better or for worse — what they say or do.

It makes a great benchmark for your like, as if, or substitution.

The fact that there is no closer tie than between a mother and child can be useful for you as an actor.

It could help you not give in when you act, assist you to stand your ground, help you tap into that pool of power you possess, help you mean what you say, help you to fight.

Putting your mother in your mind’s eye and harkening to your love for her can help keep you away from acting. You’ll be more truthful. It can be especially useful when you’re preparing a scene.

If, in a realistic improvisation in acting class, one actor is baiting the other by making fun of their mother, watch what happens to the recipient actor as the level of ridicule goes up. There will be a certain limit — a line crossed — where the actor stops acting and says “Stop!” because the insult is too much.

It’s that depth of connection that you won’t violate that is so useful.

As an actor, you must find intimate methods that assist you to believe.

“Dear dirty Dublin.”

The phrase “dear dirty Dublin” comes from James Joyce’s novel Ulysses.

An actor from Cork taught me the trigger phrase of “Dear ol’ dirty Dublin, da mess on da doorstep.” He said if I got that right, I’d be off to the races with the Dub accent.

When learning an accent or a character trait, see if you can find a simple key that helps you unlock it. Something you like, is easy to remember, and is the essence of the thing.

Could be a slouch, wide stance, slight stutter, hands closed.

Always find a starter you like.

Usually best if it’s small. A tiny diamond — containing all its qualities — cut, brilliance, colour, carat, weight.

If you start acting by trying to remember all your research and preparation, you might get overwhelmed.

(For the record, Dublin is a beautiful city that I’ve worked in and visited for many years.)

Cops, doctors, and lawyers.

When playing these iconic roles, some guidelines might be useful.

First and foremost, all of these roles are people at work, doing their jobs.

They’re good at them, they like them, it’s always just another day at work, they don’t have any other job.

The situation may be high stakes, but the protagonist is doing their usual job. That’s key for you to find the daily routine of these characters.

The situation might be a big deal, but for them, it’s no big deal.

Also, they’re cool. Everyone on TV is cool except for victims, patients, witnesses, the elderly, etc.

These iconic types can say no. They have the power of life and death whether it’s giving a death sentence in court, saving your life, or shooting you dead.

Their work is repetitive — even boring — but they always strive to be successful and — on TV — they usually are.

They’re successful while carrying personal problems — baggage.

You might be able to use like or as if relating your life to theirs.

The starting point to playing a doctor, cop, or lawyer is that it’s their job.

Tics and twitches.

As you’re reading this, you may notice that your foot is swinging regularly.

Mine is.